Question to our esteemed translators from our readers: could you please provide one or two examples of interesting translation challenges you encountered (and surmounted of course) when working on a Bitter Lemon book?

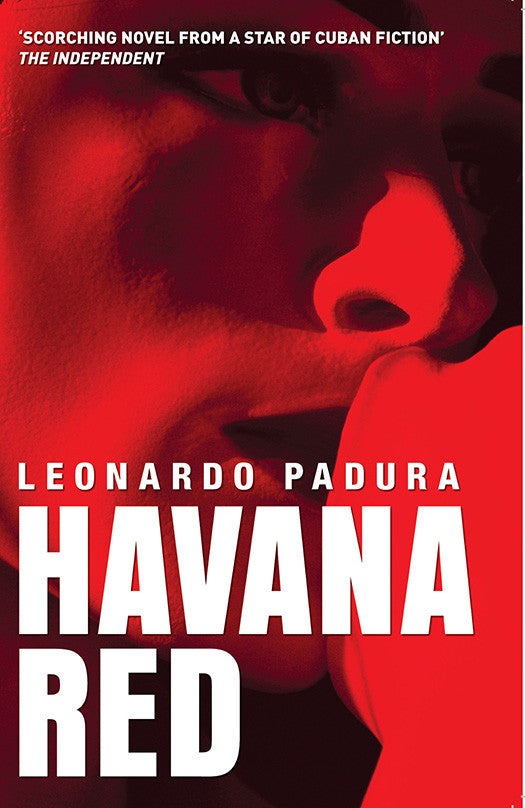

Here is Peter Bush, award-winning translator from Spanish and Catalan, about translating Havana Red, the first in Leonardo Padura’s Havana Quartet:

“The heat is a malign plague invading everything.” is the first sentence of Havana Red, the first of the six Mario Conde novels by Leonardo Padura I have translated. The narrator evokes a cataclysmic tyranny that ranges down the opening page from the physical detail of “mangy, forlorn street dogs”, “majestic trees now bent double” and “old men dragging sticks that are more exhausted than their own legs” to the more metaphysical “dark poison of despair”, “lethal vortex” and “infernal wrath” aroused as if the heat might “provoke the end of time, history, humanity and memory…” As a translator of a Conde novel, I don’t have to grapple with the recreation of the fast-moving language of a police procedural that grips readers through action-driven plots. Padura’s novels have a multi-layered language where shifts of pace are moved by other levers and the translator has to feel these rapid transitions within sentences, paragraphs and pages.

I always read a book before I translate it and that reading is the start of the translation and of many re-enactments that will enable me to attempt a re-writing. It is the way the author’s words and mine become embedded in my consciousness and unconscious, a process involving millions of choices, different kinds of research and the imaginative transformation of a book written in a unique style in a different language.

I started to write my translation and knew that in the second sentence, “The heat descends like a tight, stretchy cloak of red silk”, prefigures a detail of the murder of a transvestite actor and that the metaphorical heat oppressing Havana is particularly vicious towards anyone whose sexuality isn’t conventionally straight. The Spanish has “El calor cae como un manto de seda roja, ajustable y compacto” – “The heat falls like a mantle of silk red, adjustable and compact”, word-for-word, but, even in standard English order, “a compact, adjustable mantle of red silk”, doesn’t carry the threatening tone of the Spanish with the repeated “a” and “o”, climaxing in the imprisoning resonance of “compacto”. In the English, the rhythm becomes ominous through the use of “descends”, “stretchy” and “red”, with “stretchy” forcing the pace after “tight”. Did I think this through like this at the time? Probably not. Sometimes you do, sometimes you don’t.

However, I do remember thinking about the key transition at the beginning of the paragraph’s final sentence when Mario Conde appears in a typically Paduran move after the baroquely hellish evocation of Havana heat: “Pero ¿cómo puede hacer tanto calor, coño?” “But how the fuck can it be so hot?” In the Spanish here, the emphasis falls on the expletive as the last word, in English it must come earlier, and the abrupter the sentence the better. We all have a special relationship with expletives. I remember the fifties when their use in the public sphere in England was largely taboo and the sixties in Franco’s Spain when I was warned I might be imprisoned if I used one… Yet another aspect of language that translators must be sensitive too, and where word for word will rarely do, as here when the English “c” word just wouldn’t fit, now would it? P.B. May 2020