INTERVIEW WITH ZYGMUNT MIŁOSZEWSKI----

FIRST APPEARED IN NEW LITERATURE FROM EUROPE

There seems to be a boom in crime fiction in Poland. Why do you think the Poles are so interested in crime right now?

I think what the Poles are looking for is not so much crime as classic story-telling. They want epic novels with distinctive heroes, plenty of dialogue and sub-plots that tell a fascinating story – the sort of novels that used to win Nobel prizes for Polish writers, gave them a solid position in the world of literature and shaped the national imagination. In the West we’re known as a nation of poets, but actually we’re into adventure, romance and twists in the tail. And nowadays you find those things in particular genres, while the literary mainstream has got bogged itself down in experiments with form and self-referential whining.

But why crime in particular? It isn’t as widespread in many of the other former Communist countries of Eastern Europe, which have perhaps not yet come to terms with the idea that there can be entertaining fiction about the police and law enforcement.

I wouldn’t say crime fiction is trailing behind in the post-communist countries because the local populace still shudders at the word “police”. It’s more that nowadays the term “crime fiction” means something different from in the days of Chandler and Christie. The era of paperback detective novels and straightforward 100-page stories is over. These days crime stories are usually dynamically written psychological and social novels, where the dead body and the investigation are just one part of the intrigue. Look at Henning Mankell. Look at Stieg Larsson. Are his novels crime fiction? Or maybe spy thrillers? Harsh criticism of class relations in Sweden? A send-up of the world of big business? Or maybe the story of a wronged girl who doesn’t fit into a world where standards of political correctness are brutally enforced? By some strange quirk it has come about – in Poland and abroad – that the most interesting novels are often labeled crime fiction just because they feature dead bodies. Anyway, we’re having this conversation because I’ll be appearing at the New Literature from Europe festival in New York, which this year is all about crime fiction – that tells us something, doesn’t it? The fashion for crime fiction in Poland simply means a fashion for good literature – it just means our writers are returning to the major league internationally.

Your novel Entanglement was acclaimed as a superb crime novel, but in Poland it was the political element that stirred the most emotion, the sub-plot about a conspiracy by former communist secret service officers.

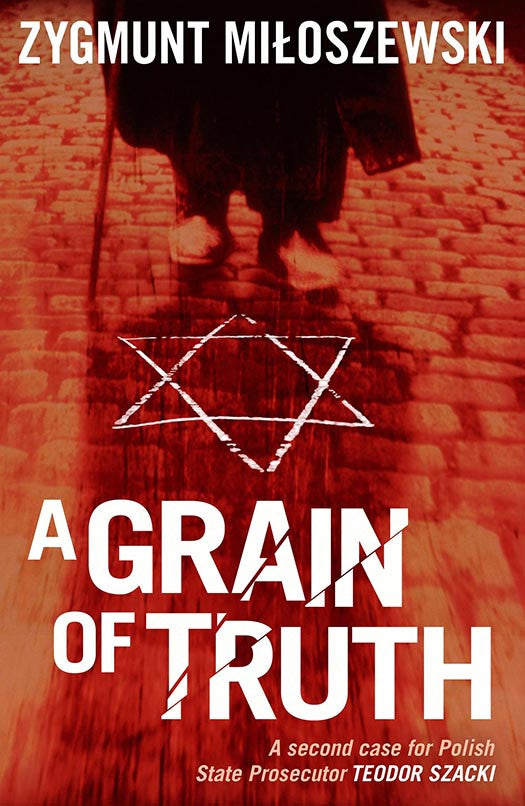

I deliberately put salt in that wound, which is still open in Poland, because for various reasons the crimes of the communist past have not all been accounted for. I don’t think it makes sense to write neutral, safe literature that doesn’t prompt any emotion. So I planned a crime trilogy featuring three major European issues that are particularly apparent in Poland, a country where various European anxieties are curiously concentrated. Entanglement is about being entangled in history and memory. In the fall, the second book, A Grain of Truth, will be out, which takes the example of extremely difficult relations between Poles and Jews to talk about the force of stereotypes and lies within Europe. The third part will be about playing the patriotism and xenophobia cards, which is still popular in a part of the world where so many nations are crammed into such a small space.

But are these still crime novels?

Mostly. A Grain of Truth is about a complex investigation, the search for a killer who resurrects an anti-Semitic legend about Jewish ritual murder in the pastoral Polish provinces. And suddenly, to the despair of Prosecutor Teodor Szacki, it turns out that all those demons which were supposed to have died out long ago were just having a light nap.

Why is your hero a prosecutor rather than a policeman?

Because you have to surprise the reader. Someone picks up a book and thinks: oh, a crime novel, the hero will be a boozy, world-weary cop in a crumpled jacket. So here we have a public prosecutor in a well-cut suit, with a stable family life. Besides which, within the Polish legal system the role of the prosecutor is very interesting – he or she prosecutes in court, but before that he or she also supervises the investigation in person.

It seems that the only commercially successful literature in translation in the United States today is detective fiction. Do you see yourself as writing for an international audience?

Yesterday it was horror, today it’s crime, tomorrow it’ll be erotic fantasy – the book market is unpredictable. That’s why I don’t write for the market, but for the reader. I want them to stay up late and to find out things they had never heard of the day before. It doesn’t matter if they live in the US or Morocco. Of course I try to write so my books are understandable everywhere, but I’m often aware that I may be introducing the reader to the existence of what we could call European knowledge. Luckily in the age of Google all sorts of knowledge is within easy reach. So far the crime format has been eminently suitable for the things I have had to say, and I’m glad I took advantage of the fashion for that genre. But soon I’ll be taking up sci-fi, though unfortunately I’m not aware of any rising fashion for space ships.

Do you think Polish authors could dethrone the Swedes as the monarchs of crime fiction?

I think they could. We’ve read about how the Scandinavian social system may be flowing with milk and honey, but has its dark side. Now it’s time to show the world the criminal Slavic soul, which includes a daring imagination, acute melancholy, and naive romanticism. And all grown on rather strange soil, a little pagan, a little folkloric, and a little Christian.

Do you think of yourself as a Polish Stieg Larsson?

I’d like to think that in a few years people will say: Larsson? Is that the Swede who was popular before Miłoszewski’s day?