Question to our esteemed translators from our readers: could you please provide one or two examples of interesting translation challenges you encountered (and surmounted of course) when working on a Bitter Lemon book?

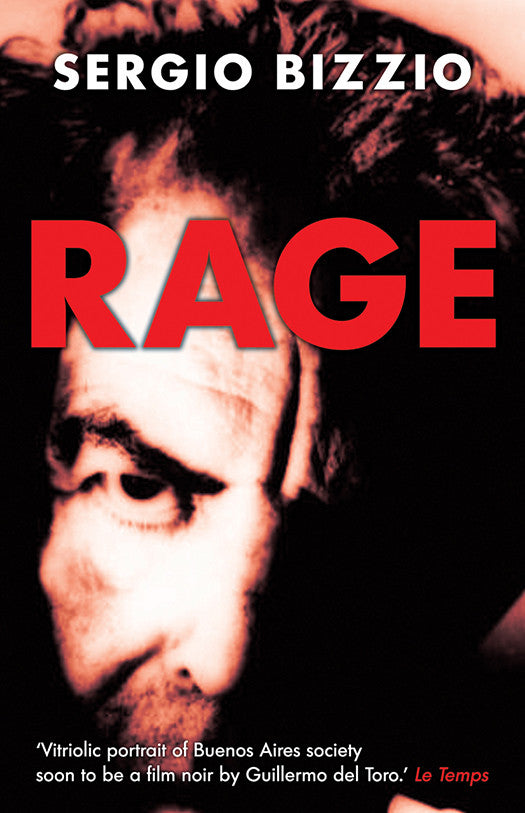

Here is Amanda Hopkinson, translator from Spanish of “Rage” by the Argentine novelist Sergio Bizzio.

A translator may suspect s/he is in for trouble when even the title of the next book gives rise to some musing. Rabia means both ‘rage’ and ‘rabies’. The original serves as a pun, for the main personage José María (to Anglophone readers - perhaps confusingly - abbreviated to María) is a young building labourer. He is also introduced as negro which in the Southern Cone is more likely to imply simply dark-skinned, perhaps just from outside town. Enraged by being exploited and disregarded, María evades his lot – and criminal detection - by secreting himself for years in the attic of a wealthy Buenos Aires family, the Blinders, with the sole companionship of a rabid rat.

Unfortunately the gift in the original title doesn’t travel in translation. It is a translation problem that can necessitate fundamentally changing the English title. In consultation with the publishers, we chose the other (very English) option: compromise. We kept the rage and lost the rabidity. [The only time I’ve been gifted a title with an English pun was in translating another Argentine author, Ricardo Piglia. His Plata Quemada became Money to Burn, which fitted well since the plot concerned the true story of a gang of bank robbers who, holed up in an inescapable apartment in a final police assault, burnt the banknotes in the bath: a final insistence that the ‘forces of oppression’ might get them but not the money they sought to recover. It brought chagrin to Piglia’s Argentine literary agent on grounds that Plata Quemada is two words and so is ‘Burnt Money’, therefore his preference should stand.]

There is a very Argentine character to Rage, in which the Blinders’ mansion can be read as a metaphor for a country plagued by social inequality and economic collapse (sounds familiar?) in the early noughties. In translation the register and tone of conversation between and beyond those deeming themselves superior required conveying idiomatically. Curiously, as internationally, swear words tend to belong within a narrow vocabulary, independent of social class.

Bizzio is primarily the author of screenplays, many (including Rage) for director Guillermo del Toro. Their focus on the descriptive and the visual is legendary and also needs to be conveyed, along with running dialogues both social and internal. Features of speech which don’t have direct English equivalents include the familiar ‘vos’ and formal ‘Ustedes’ distinctions, as forms of address for ‘you’; and the use of the diminutive. When José María falls for the Blinders’ maid, he moves from calling her ‘Rosa’ to ‘Rosita’, an informal term of endearment. When it doesn’t work to find an equivalent (‘little Rose’ sounding patronising rather than tender in English), perhaps better to retain the original.

Occasionally it is possible to go for modification or amplification. Testudo, meaning bone-headed, becomes ‘pig-headed’ when used as an insult. While everyone knows the tango – so no need to italicise, unlike the cumbia, a folk dance also mentioned - not everyone knows that it is popularly danced outdoors in the Plaza Dorrego. So the translated invitation becomes ‘to dance tango in the Plaza Dorrego’.

In a book with ample sex and violence, there is ample scope for hitting the wrong note. When I learn a new language, telling jokes or making out are the last things learnt. When I translate, I keep reminding myself that it is not only a matter of finding the right words but of transposing another culture. After all the reading experience needs to feel as natural in the English as in the original.