TLS:

"Andrew Gailey’s notes open with a quotation from Henry Asquith, asking Frances Graham “what will your biographers be able to do with a letter headed Tuesday 16th?” The question is pertinent to the subject: why did he think Frances Horner (as he knew her) would have biographers? Frances died in 1940 nearing her eighty-sixth birthday, still “quick as a weasel and quite undeaf”, but apart her from own memoirs, published in 1933, this is the first full account. As such it is a sad commentary on gender history and the limited life options for even a wealthy woman in the late Victorian age. And as an illumination of this era’s ruling class, it is, dare one say, more interesting than the book’s peg to ever-popular Pre-Raphaelitism. Frances was barely a muse, and Gailey’s political history is stronger than his knowledge of the artistic world.

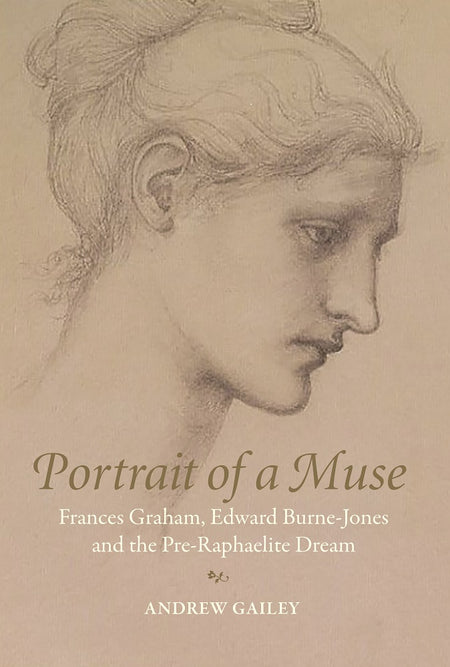

The vivacious daughter of a Scottish-born cotton magnate and wine merchant (Graham’s port) who had a passion for early Italian and Pre-Raphaelite art, Frances became a “pet” of Burne-Jones when her father was the artist’s chief patron. A fantasy romance followed (having imperilled his marriage through the affair with Maria Zambaco, the artist was careful with later flirtations) which Frances cherished all her life. She is the leading figure in the line of descending beauties in “The Golden Stairs”, shown at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1880.

She married, instead, a stolid Somerset squire named Jack Horner, whose proposal she had to prompt. Her friends included Mary Gladstone, Laura and Margot Tennant, Edith Balfour, Violet Lindsay: talented girls whose destiny was to be helpmeets, mothers and hostesses in high social and political circles. As also was Frances’s role, based at the ancestral Horner home of Mells. The autumn was dedicated to shooting parties at Longleat, Wilton and Stanway, followed by parliamentary months in London leading to the Season. She adopted aspiring Liberal politicians – a hint of the career closed to her personally – supporting Asquith, George Wyndham, and especially R. B. Haldane – and used her contacts to secure a sinecure, a London house and a knighthood for Jack. But how significant were her socio-political activities? Women like Frances were closely engaged in day-to-day Westminster events, until all vanished like Prospero’s pageant, leaving not a rack. In 1917 the house at Mells burnt to the ground and the Horners’ surviving son was killed in France.

Although Gailey does not stress this aspect, the lengthy history of Frances’s middle years bridges the time between Victorian sobriety and Edwardian hedonism – which caught the Horners’ son in its net of drink and debt. Regrettably, given that the textile arts were a major Pre-Raphaelite field and despite several fine illustrations, Gailey ignores too Frances’s achievements in embroidery, confirming the gender prejudice that deems being confidante to statesmen worthier of attention. Nevertheless, this is a valuable account of the offstage political work performed by able, unenfranchised women."