Padura was awarded the Princess of Asturias award for literature, the Spanish equivalent of the Nobel prize, on October 23. The ceremony took place in Oviedo and the King of Spain presented the awards. Previous winners include Arthur Miller, Philip Roth, Ismail Kadare and Amin Maalouf. Leonardo Padura made a touching speech, holding a baseball in his hand, about Cuba, Mantilla his beloved neighbourhood, the Spanish language, friendship and playing baseball in the streets of Havana.

Full text:

Greetings…

Here I am, and I come from Cuba. Though, rather than Cuba, I should point out that I come from a neighbourhood in the outskirts of Havana called Mantilla. I live and write there, in the same house where I was born. My father, my grandfather, perhaps even my great-great-grandfather Padura were also born in this bustling, blue-collar neighbourhood that rose up alongside the main road. There, my father met my mother, a beauty from Cienfuegos who had come to Havana driven by poverty, and he was in love with her right up until/to his last/dying breath. My maternal grandparents had been born in that central area of the island and, barring some exception, it seems that my great-grandparents Fuentes and Castellanos were also born in those parts. The reason for telling you all this is to fix the deep roots of my belonging and to establish –in the genealogical sense as well– something that is evident: I am Cuban through and through.

Both professionally and as a human being, I owe almost everything that I am to Cuba, to its culture and to its history. Because I feel profoundly a part of my island’s identity, of its spirit wrought with so many mixes of ethnic groups and creeds, of its strong literary tradition and its sometimes unbearable gregarious spirit, of the unfathomable love that we profess for baseball, and, as I am writer, I am part of the language I learned in the cradle, via which I communicate and write, the wonderful Spanish language in which I now read these words. And, therefore, to paraphrase José Martí, the apostle of the Cuban nation, I can say that two homelands have I: Cuba and my language. Cuba, with all that is to be found within and also beyond its borders; the Spanish language, because I am what I am through it, thanks to it.

With Cuba and my language in tow, I have travelled a road that has now become long and has brought me to this moment of epiphany, to this supreme astonishment and satisfaction that I cannot seem to shake off because I find myself where I never dreamed to be, although I know why I am here: simply because I am stubborn.

Yet, stubbornness notwithstanding, getting here has not been easy. In fact, being a writer has never been easy and, for me, it has been harder work than it might seem. I have dedicated many, many hours to my trade, in a terrible struggle to overcome fears and uncertainties that embrace everything: from choosing the aspects of my reality that I have wished to reflect right through to finding the right word to express that reality in the best and most beautiful way possible. Being a writer has been a blessing that I have accepted as an artistic and civil responsibility, one which has been and will continue to be arduous; I have been accompanied by much misunderstanding, marginalization even, when I was considered merely an author of crime novels, and the lash of being the way I am and writing the way I do. Forty years ago, though, I learned that there was only one formula to achieve something, at least in my case, and I adopted and practised it relentlessly: daily work. And so I can now say that, rather than two, I actually have three homelands: Cuba, my language and work.

But, I must and wish to admit here: for my three guardian homelands to have been able to bring me to this point, many people have had to come together to bring about this wonderful reality. Because not only through belonging, language and work does one live in the possible homelands of the writer and because expressing gratitude is something that adds to me.

To the creators of my home in Mantilla, I owe my life, as well as my an education as a human being and a sense of ethics which combined, in gentle harmony, both my father’s Masonic philosophy and my mother's Catholic faith. And despite not being initiated as a Mason and being an atheist, from them I learned the practice of brotherhood, solidarity and humanity among people, values that I have tried to apply to all my life’s acts. I regret that they are not physically here with me today, although I know they accompany me: my father, from the place he has been assigned by the Grand Architect of the Universe; my mother, from our home in Mantilla.

I must thank many of my fellow students and writers for their company over the years and the militant loyalty with which we have treated one another in a beautiful and difficult passage, like all of life’s courses. Although only a few of them are here today, I know that they are celebrating with me, and I can state, like Gardel on the day he debuted in Paris at the Olympia: “If the boys from the neighbourhood were here!”

To Spain, I have an unpayable debt of gratitude. Since that summer of 1988 when, as a mere journalist, I came precisely to this land of Asturias to participate in Gijón’s first Semana Negra or Noir Week, this country has opened up doors for me, a transposition which has allowed me to forge ahead and be where I am today. To the Spanish literature I knew from my studies and readings of choice was added that which I have since discovered and which has greatly changed my perceptions. Subsequently, to a Spanish literary competition, the 1995 Café Gijón Prize, I owe the possibility of having been able to create the bridge that transported one of my novels into the hands of the director of the prestigious publishing house Tusquets, thus commencing a relationship of love and work that we have maintained for 20 years and which has meant that my books have been read in every sphere of influence of the language and, from there, in more than twenty languages.

To Spain, I also owe the honour of the country’s Cabinet granting me Spanish citizenship via the naturalization procedure, an honorary recognition that has strengthened even more, if that is possible, my relationship with the second of my homelands, this language in which I express myself and write.

To the twenty-one members of the Jury who granted me the recognition I receive today, my infinite gratitude. To be worthy of this award, as everyone knows, is no small feat. The roll call of names that precede me endorses the magnitude of this award. And the fact that you have chosen me is an honour that I receive with the pride of being the first Cuban writer to achieve this distinction. And as such I receive it: as a Cuban writer and as an award to the literature and culture of my first homeland...

And to my wife, Lucía López Coll, who of course is here with me today, I can only say: Lucía, thanks for putting up with me for nearly forty years, for helping me achieve what has been and continues being the novel of my life.

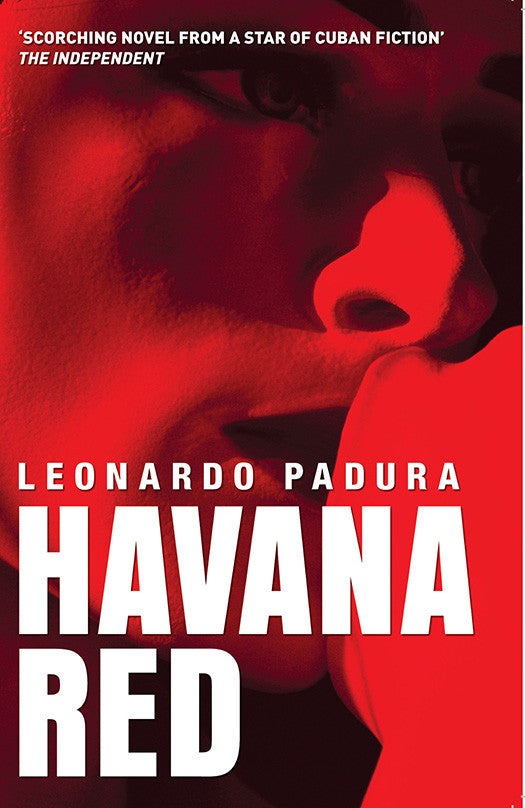

But my act of gratitude would not be complete without remembering someone who has led me by the hand to this stage. Twenty years ago, when Tusquets published my novel Máscaras (Havana Red), journalists asked me why I had chosen that name for my character. Today, thanks to the persistence of that companion-in-arms, I think my character and I have come out victorious from a tremendous battle: Mario Conde, the Cuban1, has earned a place with his resonant name in the collective imagination of this country, where he garners love, honours and readers... Thank you, Conde, for having accompanied me all these years as together we tenaciously strove to explore and reveal Cuban life and society and to understand the challenges of old age, into which we are now passing.

Today is an important day in my life –perhaps the one on which I have enjoyed the most interest from the media– and so, to have the opportunity to speak to so many people and so little time to do so, I have had to think a lot about what to say. And so I decided to talk only of truly transcendent issues, just a few, all related to love, perseverance, gratitude and belonging. Today is a day of wine and roses and that is how I wish to retain it in my memory. Because, despite everything, despite the struggles, doubts, silences and resentments, the truth is that the rewards that I owe my homelands and to all those who have helped me obtain them are a grand pretext for enjoying and sharing this happiness. And I wish to do so with the same pristine spirit with which I shared my bat, my glove and my baseball over fifty years ago with those neighbourhood friends with whom I learned to enjoy the satisfaction of success, in a simple ball game on a street in a Havana neighbourhood called Mantilla, where the heart of my homelands beats.

1 Mario Conde is also the name of a Spanish jurist and businessman who became known in Spain in the 1980s due to becoming chairman of the Banco Español de Crédito (Banesto) at the age of thirty-nine. His business career was cut short in December 1993 by the financial scandal known as the “caso Banesto”, for which he was sentenced to twenty years in prison by the Supreme Court.